I’ve seen many articles and discussions online discussing the merits of merge and rebase when integrating parallel branches into the main branch. It seems there are two camps arguing “which is better” when in reality, both have their own use cases.

The task we need to accomplish is to determine which workflow is right for your project. This article will attempt to provide an overview to the different workflows, and explain when merge and rebase are the more appropriate workflow to use.

The Simplistic Branch Workflow

aka the GitFlow / Branch-Merge-Merge Workflow

Software development teams have a typical way of doing things, but all have a main integration branch (I’ll call it “Master” for the remainder of this article) that receives feature branches.

Feature branches originate from Master, active development is performed along the feature branch, and when the feature is complete, it’s combined back into Master.

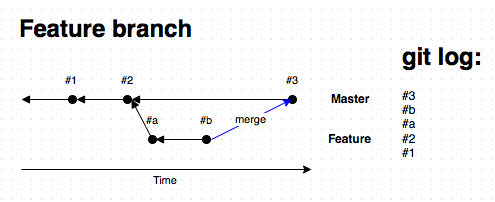

I call this workflow the “GitFlow / Branch-Merge-Merge” workflow. The history of events for this simplistic workflow are as follows:

on Master:

- commit #1

- commit #2

on Feature:

- commit #a

- commit #b

on Master:

- merge feature

--no-ff

This produces the following graph:

This workflow performs well for a single developer because while the feature development occurred on the feature branch, the sequence of events occurred linearly. Importantly, no changes occurred on Master while Feature branch was changed.

When development occurs in parallel on the upstream branch (ie. Master), either by the developer, or a co-developer, the history gets more complicated.

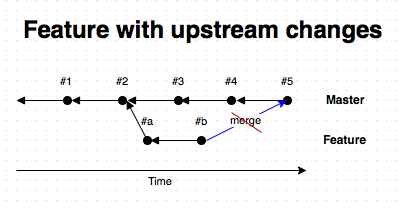

For this example, we’ll pretend to be a single developer working on both branches in parallel, we use the following sequence:

on Master:

- commit #1

- commit #2

on Feature:

- commit #a

- commit #b

on Master:

- commit #3

- commit #4

on Master:

- git merge feature

--no-ff

This produces the following graph:

Graph of a typical git workflow. Numbered commits occur along Master. Alphabetized commits occur along Feature.

In the above scenario the developer runs into the problem where Feature commits #a and #b were done independently of Master commits #3, #4 and #5. This merge will fail.

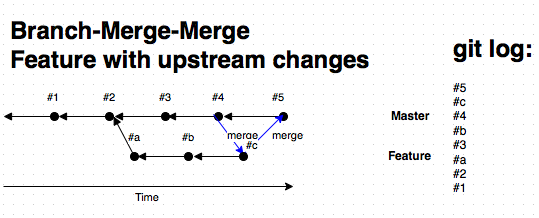

To solve this problem, the developer must first merge the upstream changes in Master into feature branch Feature. To accomplish this, the developer must switch into the feature branch and merge in the changes from Master. The developer must then switch back to Master and merge the changes from Feature into Master. Use the following sequence:

on Feature:

- merge master

on Master:

- merge feature

This produces the following graph:

Note how the final git log interleaves the commits on Feature between commits on Master.

I call this workflow the “Branch-Merge-Merge” workflow because in the most general case — the workflow begins with a branch, requires an upstream merge into the feature branch prior to merging the feature branch back into the master branch.

Looking at the above graph, feature branch Feature has been merged successfully into Master, but the git log shows an interleaved sequence of commits between Master and Feature that make debugging complex.

In the case where branch Feature introduced a bug into the Master branch, a rollback will be difficult because of how the commits are interleaved. In the case where the bug was introduced in Feature branch commit #b, the maintainer of Master branch would need to roll-back commits #6, #c, #5, #4 and #b. This is a difficult roll-back because Master branch features #5 and #4 were rolled back in the effort to roll back to Feature branch feature #b. We’ve thrown some of the baby out with the bathwater.

One way to address the problems with this particular scenario is to merge in the Feature branch as a single commit appended to the Master branch, rather than as a set of interleaved commits within the Master branch. This brings us to the next workflow.

Branch-Merge-MergeSquash Workflow

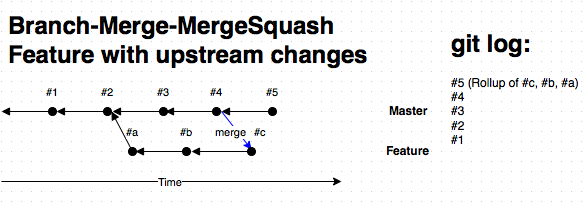

This workflow attempts to address the shortcomings of the workflow above by appending feature branches as a single commit at the end of the integration branch.

For this example, lets pretend to be a single developer working on both branches in parallel (as I did above), we use the following sequence:

on Master:

- commit #1

- commit #2

on Feature:

- commit #a

- commit #b

on Master:

- commit #3

- commit #4

on Feature:

- merge master

on Master:

- git merge feature

--squash

This produces the following graph:

The git log sequence of events shows a linear series of feature integrations.

Looking at the above graph, feature branch Feature has been merged successfully into Master (although the graph doesn’t show a merge line) at commit #5. Importantly, the git log shows a linear sequence of commits, each indicating a complete feature integration. The squash flag has collapsed Feature branch commit #a, #b and #c into single commit #5.

In the case where branch Feature introduced a bug into the Master branch, a

rollback will be as simple as running git reset --hard HEAD^ because of how

the Feature branch was a single commit appended onto Master. In this scenario,

the Master branch maintainer would tell the Feature branch maintainer to fix the

problem, and they could attempt the merge once the issue was fixed.

I recommend this workflow as a best-practice in cases where the feature branch will be shared (eg. pushed to GitHub, shared with other developers.)

A potential downside of this workflow is the potential confusion caused by the origin commit of the Feature branch. Feature branch origin is located at commit #2, and merged at commit #5. This is additional cognitive load on the Master branch maintainer when it comes time to merge the feature branch into Master. A simplified workflow could solve this by having the Feature branch simulate its origin commit at commit #4 prior to merging into Master. This would reduce cognitive load on the Master branch maintainer.

Branch-Rebase-MergeSquash Workflow

This workflow is popular with open source projects where the job for the Master branch maintainer involves multiple feature branch integrations on a daily basis.

This workflow is designed to make feature branch merges much simpler and easier to roll back. The main idea is that each feature branch is a simple append to the end of the Master branch. No merge is simpler than and append-merge.

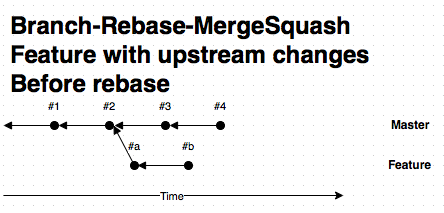

For this example, lets pretend to be the same single developer working on both branches in parallel (again, as I did above), we use the following sequence:

on Master:

- commit #1

- commit #2

on Feature:

- commit #a

- commit #b

on Master:

- commit #3

- commit #4

on Feature:

On the Feature branch, the graph appears after commit #2 prior to rebase.

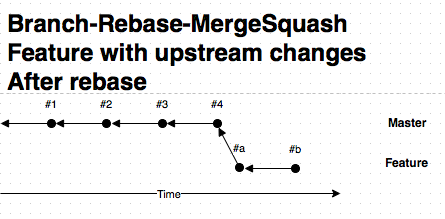

- rebase master

After rebase, Feature branch commits #a and #b originate from parent commit #4

We have now changed the origin commit of branch Feature to commit #4. This sets up future merges of the Feature branch to append directly to the end of Master branch.

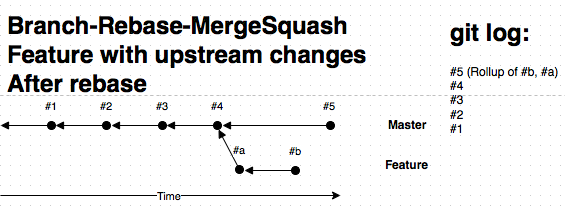

on Master:

- merge feature

--squash

We’ve now switched to the Master branch, and merged in the rebased Feature branch, appending a single commit #5 to the end of the Master branch containing all of the Feature branch.

This produces the final graph:

After merging the Feature into Master, commit #5 containing the final result of all Feature branch commits #a and #b.

The final sequence of events on the Master branch read cleanly, showcasing only past feature branch integrations. Each feature branch originated directly from the latest commit, making it seem like the feature is a simple fast-forward append onto the latest commit.

It’s worth pointing out the Branch-Merge-MergeSquash and Branch-Rebase-MergeSquash workflows both result in the same final sequence of commits. The major benefit of the Branch-Rebase-MergeSquash workflow is that its’ branch origin appears much later in the history, reducing cognitive load on Master branch integrations.

I recommend this workflow as a best-practice when the developer is working alone on a feature branch, as well as just-prior to merging the feature branch into the master branch.

The

downside of this workflow is when sharing a feature branch after a rebase.

Pushing to GitHub will require the --force flag, and anyone else working on

the feature branch will see changes to the branch history when they pull an

update. This is why I don’t recommend this workflow for shared feature branches.

Conclusion

I see huge benefits in collapsing feature branch commits into the master branch with — — squash, both for simplicity sake, clarity, and reduces cognitive load when the master branch maintainer needs to merge in big features. Additionally it makes the use of git bisect much easier.

I love the advantages to using git rebase to merge in upstream changes while working on a feature branch, but it seems people need to use the workflow in practice before they can understand its benefits. Give it a shot, you might like it.

All three workflows have been published to GitHub

This article was originally published on Medium.com