Khoury College of Computer Sciences

Northeastern University Boston, MA

This paper documents the creation and testing of a game playing artificial intelligence (AI) agent program. The agent is designed to play a game of Connect Four by Milton-Bradley. The game is played by dropping pieces into a game board consisting of a grid of 6x7 slots. The object is to make a vertical, horizontal or diagonal line of four pieces before the opposing player does. The agent designed in the current study is able to play against a human opponent or against another AI agent.

Introduction

In this chapter the rules of the game Connect-Four are described, as well as the task environment. We also introduce a naming convention used throughout this text.

The Rules of the Game

Connect-Four is a game for two persons. Both players have 21 identical pieces. In the standard form of the game, one set of pieces is red and the other set is yellow. The game is played on a vertical, rectangular board consisting of 7 vertical columns of 6 squares each. If one piece is put in one of the columns, it will fall down to the lowest unoccupied square in the column. As soon as a column contains 6 pieces, no other piece can be put in the column. Putting a piece in one of the columns is called a move.

The players make their moves in turn. There are no rules stating that the player with, for instance, the red pieces should start. Since it is confusing to identify for each new game the color that started the game, we will assume that the sets of pieces are colored white and black instead of red and yellow. Like chess and checkers (and unlike go) it is assumed that the player playing the white pieces will make the first move.

Both Players will try to get four connected pieces, horizontally, vertically or diagonally. The first player who achieves one such group of four connected pieces wins the game. If all 42 pieces are played and no player has achieved this goal, the game is a draw.

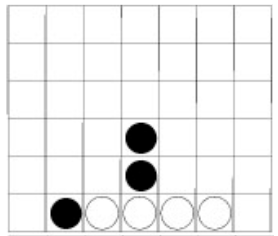

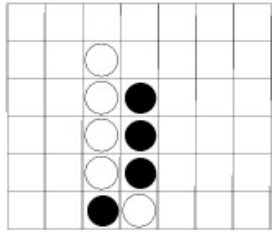

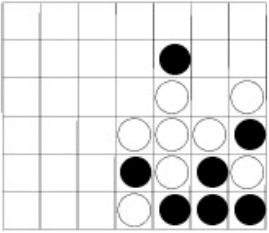

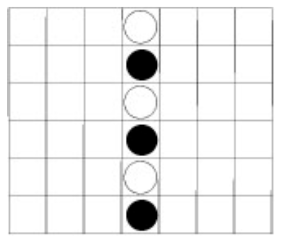

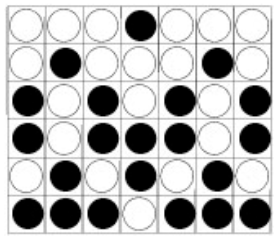

Diagrams 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 show positions in which White has won the game:

In the position of diagram 1.1, White has made a horizontal winning group, while his winning groups were respectively vertical and diagonal in the other two diagrams.

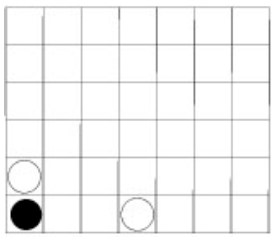

A possible drawn position is shown in the diagram 1.4:

Task Environment

The goal of this study was to create an agent to play the game Connect Four. The rules for the game were taken from the classic game of Connect Four. However, the environment and the agent program was created from scratch. On the surface the program functions as a simple Connect Four game playable between two human players.

In order to make an appropriate agent design, the task environment must first be identified and described. Table 1.1 is a PEAS description of this task environment. The task environment can be further categorized by several other factors, such as observability, number of agents, etc. These factors are described in Table 1.2.

| Agent Type | Connect Four Playing Software Agent |

|---|---|

| Performance Measure | Put four pieces adjacent or diagonal to each other, prevent opponent from doing the same. |

| Environment | Game Board, Agent’s pieces, and Opponent’s pieces. |

| Actuators | Piece placing function. |

| Sensors | Direct access to the state of the board. |

Table 1.1 – A PEAS description of the task environment.

| Environment Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Fully Observable vs. Partially Observable | The Connect Four environment is fully observable. The environment consists of the board, which has constant dimensions, and the pieces, which belong to either the player or the opponent. The agent has access to all of this information. |

| Deterministic vs. Stochastic | This environment could be considered deterministic, as there are no random elements at work here. The only unknown is the actions of the opponent. Therefore, the environment can be classified as strategic. |

| Episodic vs. Sequential | The environment could be either episodic or sequential, depending on the algorithm the agent uses. If the algorithm calls for random placement of a piece, then the environment is episodic. However, if the algorithm is more sophisticated, calling for prediction of the opponent’s moves, then the environment is sequential. |

| Static vs. Dynamic | This environment is fully static. Time is not a factor in making the decision as to where to place pieces. Once it is the agent’s turn, the state cannot be changed until it makes its move. The agent is also not penalized as a function of decision time. |

| Discrete vs. Continuous | Connect Four is a fairly simple game with a finite, albeit large, number of different states. Therefore, the environment is decidedly discrete. |

| Single agent vs. multi-agent | In this game, there are two agents at work. From the point of view of the AI agent, there is itself, and another agent. The other agent can either be a human player or another AI agent, which may or may not use the same algorithm. Since both agents (be they human or otherwise) are out to maximize their own performance measure and minimize their opponent’s, the environment is classified as competitive multi-agent. |

Table 1.2 – Detailed description of the task environment properties

Naming Convention

In order to be able to talk about a position, it is useful to give each square a name. We have chosen to use a convention as used by chess players. The 7 columns are labeled ‘a’ through ‘g’ while the rows are numbered 1 through 6. In this way the lowest square in the middle column is called d1.

It is now possible to make a list of the moves made during a game. For the game diagram 1.1 this could have been:

- d1, d2

- c1, d3

- e1, b1

- f1, White wins.

It is also easy to use the names of the squares to show where the winning group

was created. In diagram 1.1 the winning group was on squares c1, d1, e1 and f1.

Since the squares must lie on a straight line, it is enough to specify the two

endpoints of the group. In this case the group can be identified with c1-f1. In

general the notation square1 square2 will be used to identify all squares on

the line with sqaure1 and square2 as endpoints.

Complexity Analysis

In this chapter we show why a brute force approach will not be successful at this time.

Complexity of the Game

In order to get an idea about the complexity of the game an estimate is presented of the number of different positions that can be achieved, if the game is played according to the rules. A position that can occur during a game is called a legal position, while a position that cannot be achieved is called illegal.

Each square can be in one of three states: empty, white or black. Therefore it is easy to see that the number of possible positions is at most 342 (≥ 1020). This upper bound is a very crude one, and can be brought into better proportions.

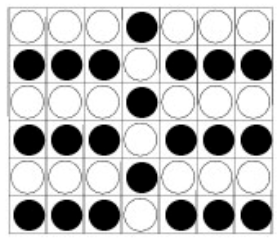

If the total number of occupied squares in a given position is odd, the number of white pieces is one more than the numbers of black pieces. If the total of occupied squares is even, these numbers are equal. Furthermore, if a column contains an empty square, all squares higher than this square are also empty. If a position contains four connected pieces, the position concludes a game. Since the last move ended the game, at least one of the four squares in the connected group must be the highest filled square in its column. If this is not the case, or both players have connected four pieces, the position is illegal. If one player has more than one connected group this position can only be legal if these groups share a square that contains the last piece played. In the calculations we are going to make, we do not rule out positions in which are illegal for the reasons mentioned above. We also do not rule out positions that are not legal, because they cannot be achieved, during normal play. Diagram 2.1 shows such a position.

Although the position looks perfectly normal, it is clear that Black has made the first move. Therefore it is not legal simply because white is supposed to move first according to the rules.

We have calculated the number of different positions, including all illegal positions which contain too many connected groups of four pieces, and illegal positions as shown in diagram 2.1. For the standard 7 x 6 board, an upper bound of 7.1 x 1013 is found.

To determine the amount of memory needed to construct a database for Connect-Four this upper bound is useful. In order to show that such a construction takes too much memory, we need a lower bound instead of an upper bound. If we want to find a good lower bound of the number of possible positions, we have to make sure that each position we count is legal. Therefore all positions which cannot be achieved during normal play, e.g. diagram 2.1, should be ruled out. Diagram 2.2 illustrates the difficulties we are faced with in determining if a position is legal.

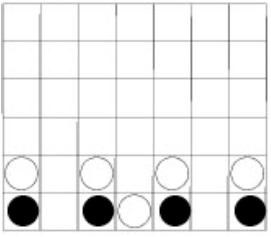

The position of diagram 2.2 is a draw. Although at first sight it might look like a normal position, it cannot be achieved during normal play. This can be seen as follows: the first move White made must have been d1. If Black played as his first move one of b1, d2 and f1, there is no possible second move for White. Therefore Black’s second move was one of a1, c1, e1 and g1. Suppose Black played a1, White then must have played a2 as second move, giving the position of diagram 2.3:

Now Black still cannot have played b1, d2 or f1, for the same reason as before. The move on a3 is not possible either. Therefore Black must have played one of the remaining c1, e1 or g1. After one of these, and after White’s answer to it, the position did not get any better. The furthest we can get with this game is shown in diagram 2.4.

In this position Black has to move. For all seven columns, the lower two squares should be filled by black pieces. Therefore after the next move of Black there is no move White can make that will eventually result in the position shown in diagram 2.2. Therefore that position is illegal.

This diagram shows that it can be rather difficult to detect if a position is illegal. It is equally difficult to show which of the positions are not legal because more than one group of four connected pieces is present. We therefore assume that a database should contain a large number of illegal positions. We believe that in that case the order of magnitude of the upper bound presented before, is a good estimate for the magnitude of the database. This number is by far too big to think seriously about making a database for Connect-Four. To see this, we have to consider the number of positions that must be stored at the same time when we build the database. When a retrograde analysis is applied, as has been done for many endgames in chess, we need not necessarily store the positions consisting of, say, 20 pieces, as long as we have not yet determined the value of all positions of 21 pieces. When we have determined the value of these positions, we no longer need the positions consisting of 22 pieces or more. Therefore we only need to be able to store all positions of n and n+1 pieces at the same time. For the 7 x 6 board, this means that we must be able to hold all positions of 36 and 37 pieces at the same time, a total over 1.6 x 1013 positions. We can store the value of a position in 2 bits, since we have 4 possible states: win for White, win for Black, draw or not checked (we can use the address of the 2 bits as identification for the position). This way we need at least 4 Terabyte. Therefore making a database does not yet seem realistic.

Development

Interface

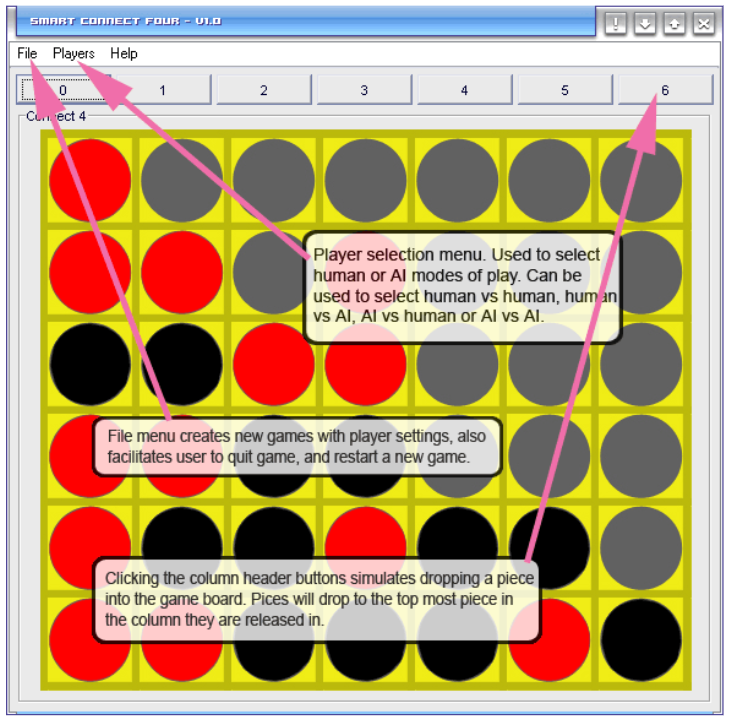

The interface of the game program consists of two parts, the menu, and the game board. The menu gives the user access to the game controls, such as setting which AI algorithm to use, and which players will be controlled by humans and which by AI agents. One interesting feature of this particular design is that one can begin a game with two human players, and set up the board any way they like. Then one or both of the players can be switched to AI agents, in order to see how they react to different initial configurations of the board.

Once the players are set, the user can begin a new game. The game board is set to the initial configuration of all empty squares. Players then take turns dropping pieces into the 7 columns of the game board. Human players make moves by clicking the button above the desired row. This design was favored over other interfaces, such as clicking directly on the game board, partially because of time restraints, and partially because it more closely approximates the way the real game is played, by dropping pieces into the top of the board. The AI agents, of course, automatically make their moves, so their pieces appear very soon after the opponent makes their move. Since the AI agents are very fast at making their decisions, AI vs. AI games of Connect Four are for the most part very short.

When the game is over, a window pops up that notifies the user of the outcome. If the game results in a win for some player, the message states that that player has won. However, if the game ends in a draw, then this message is relayed to the user instead. From that point, the user can either quit or begin a new game.

As a side note, in early versions of the program, there was one other form of interface present. The list of moves in sequential order was output to a text window, along with system messages such as which player was victorious. This list of moves proved very valuable for the debugging process. At one point, when pitting AI agents against each other, the program became stuck in an infinite loop. It was very beneficial to be able to see what moves led up to the loop and what moves the AI was trying to make during the loop.

Design

This design is both intuitive and minimal. The GUI was written in Java/Swing, a toolkit provided by Java, as seen below in diagram 3.1.

Artificial Intelligence

The computer AI opponent of the program is configurable to different difficulty levels. Each difficulty level represents a different algorithm. There are four different difficulty levels in this version of the program; Random (easy), Defensive, Aggressive, and Minimax (difficult).

Random AI

The Random AI algorithm simply places pieces randomly each turn. This algorithm can be defeated easily by human players and by the other AI algorithms. It is also the only one that is non-deterministic. Since it randomly places pieces, the move progression will be different each time this algorithm plays. As described below, the Random algorithm is the only one with this characteristic.

Defensive AI

The defensive AI algorithm uses a heuristic function to determine what the next move should be. It looks at the current state of the board and assigns a value to each of the available moves. The higher this value is, the more dangerous it is not to move there. For instance, if the opponent has three pieces in a row, a value of 8 is given to the space that would complete the opponent’s four-in-a-row. If the opponent has two pieces in a row, a value of four might be given to the adjacent square. The point of this algorithm is to block the opponent from getting four in a row at all costs.

Aggressive AI

The Aggressive AI algorithm uses the same type of heuristic function used by the defensive algorithm, with one key difference. The defensive algorithm only applies the heuristic function to the opponent’s pieces on the board. The aggressive algorithm applies it to both the opponent’s pieces and its own pieces. Thus it simultaneously defends against potentially losing situations by blocking the opponent from winning, and makes offensive moves maximizing the number of pieces it has in a row. Skilled human players are still able to defeat this algorithm fairly easily, however, since it does not look very far ahead in the game tree.

Minimax AI

This algorithm was initially going to use the minimax algorithm (as implemented in Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach) to search the game tree for the optimal move. However, the tree proved to be too massive to search in this way, due to computational limitations. One possible solution to this problem was the alpha-beta pruning algorithm, in which game subtrees are eliminated to cut down on the number of computations. However, this idea was passed over for a simplified version of the minimax algorithm. Instead of searching the entire game tree, the algorithm used in the final version of the program only searches the tree up to a certain point. So, in effect, the algorithm is looking four moves ahead and making the best move based on that knowledge. The decision to limit the lookahead to four levels was made because it is about equal to the number of moves a skilled player can look ahead, and it is a good match for the current power of processing technology. Thus the Minimax AI is a good match for a skilled human player.

Results

One of the primary functions of this study was to learn about how the different AI algorithms perform against one another. Due to the short length of the matches played between to AI players, many trials were able to be conducted. Table 5.1 is a brief summary of how the different algorithms interact.

| Condition | Winner (most often) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Random vs. Any Other | Any other | Since random play is seldom successful, Random AI is most often defeated. However, it can and sometimes does win against stronger AI. |

| Defensive vs. Defensive, Aggressive vs. Aggressive | Draw | It was hypothesized that whichever player went first would win most often. However, more often than not the game ended in a draw. For those games that did not end in a draw, no player won significantly more than the other. |

| Defensive vs. Aggressive | Aggressive | Since Aggressive AI takes into account more of the state than the Defensive, Aggressive will always prevail. |

| Defensive or Aggressive vs. Minimax | Minimax | Since Minimax is able to look ahead four moves, it will usually defeat both Defensive and Aggressive. There are some instances where the game will end in a draw. |

| Minimax vs. Minimax | Player 2 | For some coincidental reason, when Minimax is pitted against itself, the second player always wins, and the same game is always played. This may be due to the fact that the entire game tree is not searched, so the algorithm is not perfect. |

Table 5.1 – A summary of the results of AI vs. AI games.

Conclusion

Above all else, this study was designed so that the authors could learn more about AI. This goal was successfully accomplished. The specific area in which the most experience was gained is that of computer game playing agent design. While the algorithm best suited to success may be impossible to execute with current technology, other algorithms are just as suitable to make for an interesting playing experience. This is an important game design concept, because more often than not, people want to win games they play. Therefore, if the computer AI always wins because the algorithm is perfect, the game will suffer from lack of human interest.

Heuristic algorithms like the Defensive and Aggressive algorithms outlined in this study are very well suited to solve this problem. Since they do not always win, but sometimes trick a human player, they retain a human player’s interest. As long as no one programs a heuristic algorithm to become frustrated at losing, they will remain one of the best solutions to a computer game-playing problem.

References

Russell, S., Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence, A Modern Approach. Third Edition Pearson Education, Inc. Prentice Hall. Print. 2003.

Flanagan, D. Java in a Nutshell. Third Edition. O’Reilly & Associates, Inc. Print. 1999.

Knudsen, J. Java 2D Graphics. O’Reilly & Associates, Inc. Print. 1999.

Milton-Bradley, Inc. Connect Four Game, Hasbro, Inc.