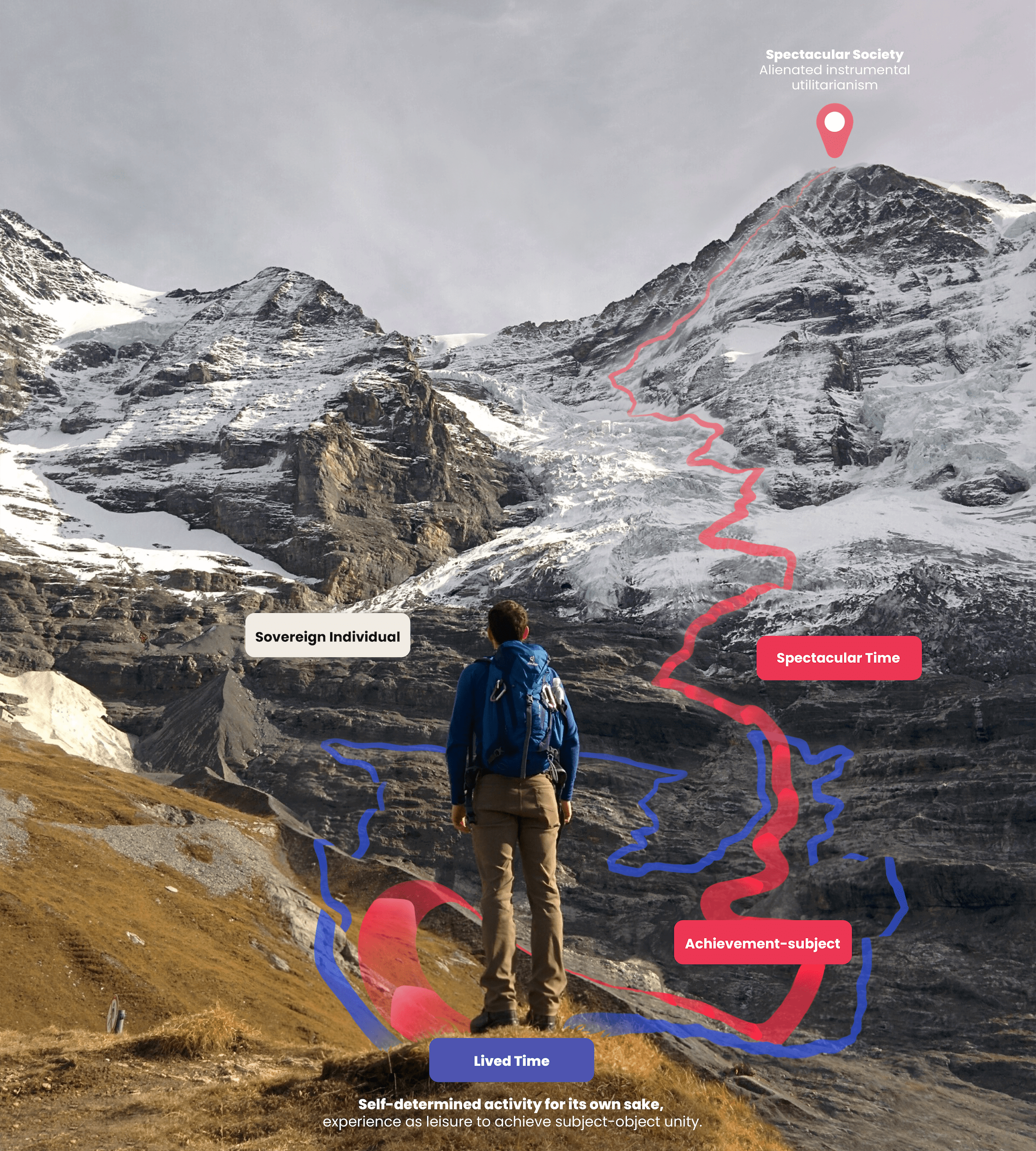

We stand on the brink of a precipice. In front of us lies a society driven for the sake of productivity, the mechanics increasingly directed by artificial intelligence to serve corporate interests. Behind us lies centuries of experiments in social organization that provide the historical and material foundation of society. Some failed with communism’s collapse in 1991, while the capitalist experiment shifted to the authoritarian ‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics’ in the east, or the more subtly coercive neoliberal experiment in the west. This experiment has raised many out of poverty, and yet has not improved the quality of life. As “We stand on the brink… we peer into the abyss…” (Poe, 2022).we peer into the abyss,1 many grow sick with emergent This is not to say that these diseases are naturally occurring facts, nor that these diseases do not exist. They are really experienced diseases that are contingent upon existing conditions of neoliberal capitalism.social diseases—anxiety, depression, exhaustion, and burnout. These conditions are a symptom of a way of life that lacks direction. With the gradual shift to secular life, we’ve turned away from communal practices that provide spaces and times that lead to human flourishing. These practices included holidays in which contemplation, prayer, and meditative practices were observed— e.g.like Shabbat and Sundays. These were times allocated to prayer, creative play, leisure, reflection, rest, and quiet solitude that are no longer protected or made available to greater society. Liberal democracies have abandoned the practice of community-rest, pushing it into the private domain of the individual, but what they have lost is leisure and the communities that exist there. The position presented here is not a call to return to some golden past, or a renewed spiritual order, but a historical account of the perspectives that led to the loss of leisure. It explores a revitalization of times and spaces for human flourishing that were formerly protected by a spiritual order, but can equally be rooted in secular thought. I propose points of resistance to a dominant social order that seeks to continually capture the vestiges of free time.

At this juncture, society can collectively decide what the future will hold for humanity—we can determine what that looks like, what we’re building, and to what ends. If we do not rise to this challenge, then the instrumental power that has emerged out of neoliberal capitalism will decide our future for its own banal ends. Together we can decide if we want increases in productivity to appear in the form of profits for the few, or as surplus time allocated to the many—the latter of which can be used for leisure and the concrete activity of creating a brighter future for all.

The Historicity of Time

’Time’ is natural, physical, and spatial; it exists independently of humanity.

‘History’, however, is humanities

Bunyard 2018, p. 216.awareness of its existence within a temporal reality—only arises with the emergence of human beings

,2

and is shaped by humanity.

The great arcs of history are determined by the rulers of their period, and individuals are capable (to a certain extent) of generating their own personal narratives within that period.

Bunyard 2018, p. 4.History, therefore, is a process directed by human agents to shape their world, and create their own identities through that activity

.2

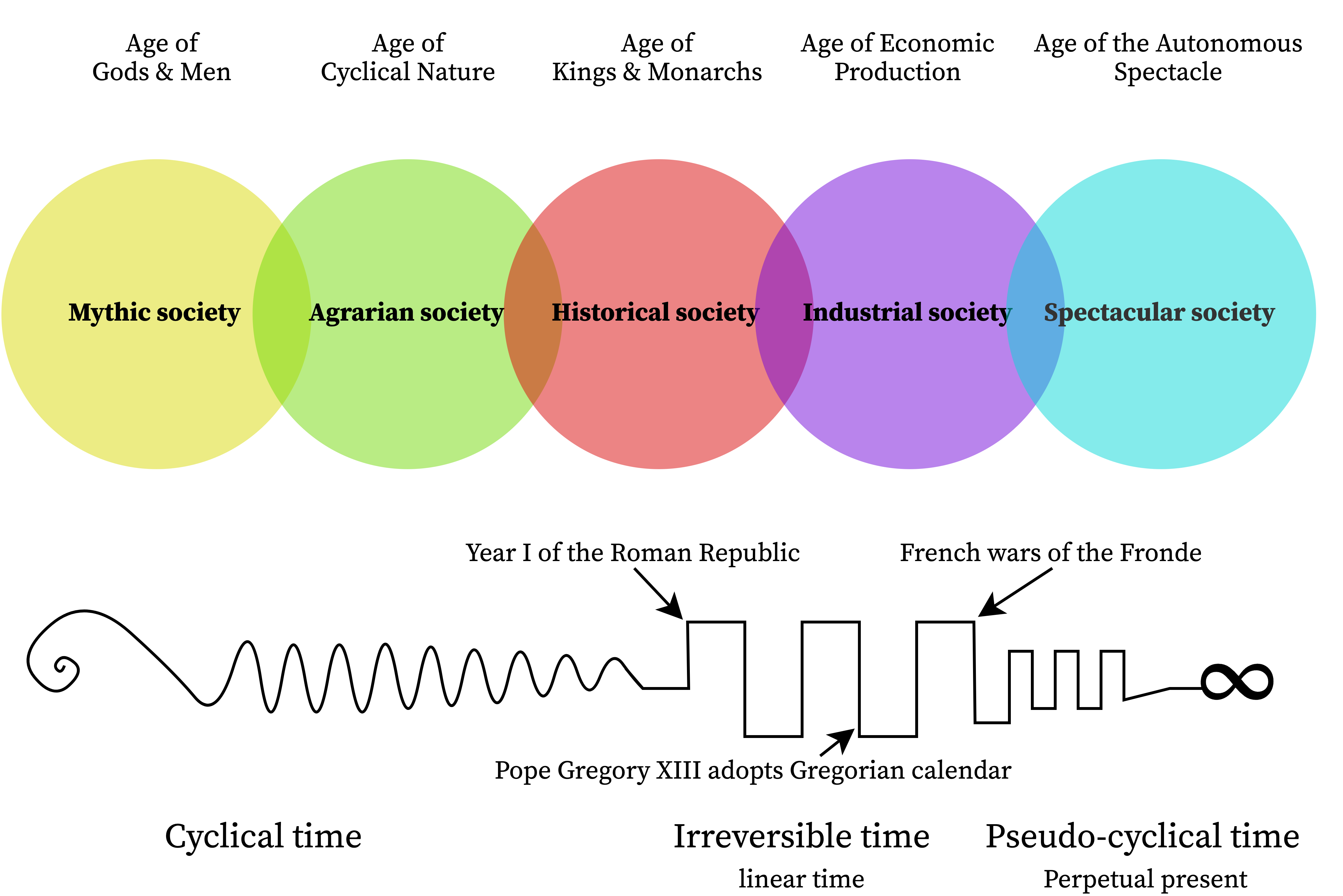

In order to establish an understanding of the perception of time across history, I will begin with a periodization that draws from the philosophical anthropology of Guy Debord in See chapters V. and VI.The Society of the Spectacle.3 Debord presents a series of historical periods characterized by social structures that engender different perceptions of time called ‘temporalities’. The following table lists these distinct periods. Each age is mediated by a form of social organization, and that organization generates a corresponding temporality. I will describe each in turn.

| Age | Social organization | Temporality | Related periods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Gods & Men | Mythic society | Cyclical time (early) | The Neolithic Age to the Early Bronze Age. Prior to the First Egyptian Dynasty, and before the invention of agriculture. |

| Age of Cyclical Nature | Agrarian society | Cyclical time (late) | From the invention of agriculture to the invention of written language. Early Bronze Age to the Middle Bronze Age. |

| Age of Kings | Historical society | Mythical time / Irreversible time | From the emergence of cities and the invention of specialization: nobility, warriors, priests. From the Etruscans to Roman Republic to the Holy Roman Empire. From the Zhou Dynasty to Ming Dynasty. The emergence of mercantilism & nation-states. Late Bronze Age to Late Middle Age. |

| Age of Economic Production | Industrial society | Chronological time | The Enlightenment, the era of the nation-state and the industrial revolution. Late Middle Age to the end of the Machine Age. |

| Age of the Autonomous Spectacle | Spectacular society | Pseudo-cyclical time / Spectacular time / Perpetual present | Post-War Era, Information Age, the emergence of global communications, globalization, and mass media. |

Each age describes the dominant forces that structure daily life—the A zeitgeber is an external cue that entrains or synchronizes an organism’s biological rhythms. These are natural factors like light, temperature, seasons, but can include social cues like work schedules or gig apps.zeitgeber, which shape perceptions of time. There is overlap between ages, both temporally and spatially. An age is more keenly experienced in the city than in the countryside. The procession of one age to the next doesn’t entail that the previous age has ended, but that its’ forces have receded to the background—they become infrastructural rather than hegemonic. To illustrate, the mythic narratives that arose from the Age of Gods & Men remain with us in the form of stories and metaphors that provide us with rich cultural allegory. In another case, the Age of Kings had no definitive end, in fact, relics like the Queen of England still exist, but monarchy is less important these days, and thus has become merely cultural. Institutions like religion, which previously dominated social organization have similarly receded. In some sectors, secular life has completely subsumed spiritual life, and spiritual life is relegated to the private domain of the individual. The ages of the past are still with us, but they’ve become a given, received culture, one that is taken for granted—its issues and contentions are largely settled debate, but remain relevant. Past ages become social and cultural foundations—but just like a buildings’ foundation, they are more ossified and unchanging. The hegemonic age, however, dominates in its effects on daily life, it organizes social institutions, it’s open to continual evolution and debate, and is always changing and dynamic.

The Age of Gods & Men is the period before prehistory. It is accessible only through the archeological record and surviving oral traditions. This is a period in which nature recurs with time, the coming and going of the seasons and celestial bodies. This is a Mythic society prior to the mastery of language. Mythic society was a directly lived experience, created by their own direct actions, one in which all individuals directly participated—by necessity. The hegemonic temporality associated with this age was Cyclical time. Cyclical time shaped peoples understanding of time as they encountered naturally cyclical conditions, repeated along every moment of their nomadic journey with the seasons and according to the migratory patterns of wild game and local flora. The spatial modality of this period is characterized by territories that were undifferentiated and therefore uniform—that is to say, hunter-gatherers didn’t stay in a single territory long enough to shape their environment. This age applied to human societies until the invention of agriculture, animal husbandry, and the emergence of subsistence farming.

The Age of Cyclical Nature is characterized as a time that is proto-historical. When agriculture began, communities invested labor into the land, The Clearing (die Lichtung) is Heidegger’s concept of the open space where Dasein creates themselves.clearing4 it for planting and imbuing it with content. This attached the community to space, and therefore enclosed the community within cultivated property—one surrounded by a differentiated region of uncultivated lands. This was a shift from the nomadic seasonal cycle, returning people to undifferentiated but similar places and a familiar set of gestures in time (planting, harvesting, etc) that were attached to a single place. Agrarian society generated the spatial modality of “differentiated property” and “undifferentiated lands”. The transition from the pastoral nomadism of the Age of Gods & Men to settled agriculture marked the end of an idle and unattached freedom, and the beginning of labor. The Agrarian society and agricultural mode of production is governed by the rhythm of the seasons, and as such is the implementation of Cyclical time in its fullest development.

The Age of Kings emerged from the practice of permanent agricultural settlements, and the growth of cities.5 The Age of Kings is characterized by the division of social classes, each specializing in a different aspect of the total production of society: farmers, warriors, priests, and the nobility. The nobility organized social labor on the basis of the accumulation of wealth in the form of Surplus value during the Age of Kings was the total amount of crop remaining after farmers fed themselves and paid taxes.surplus value. This class appropriated the temporal surplus value that resulted from the exploitation of the farming class. Surplus time was invested into the development of a new form of power: the control of spatial territory and the development of history that was at the sole discretion of the nobility. The development of history is a new form of power controlled by the nobility over the direction, management, and recording of historical time. This is a power inaccessible to the laboring and agrarian classes. This power is most visible in the historical chronicle—a story narrating the events deemed most significant to the ruling class, and often the only recorded history until the invention of the printing press. The nobility used this instrument to establish the forward progression of their historical time by recording its past with writing. Mythical time is the realization of the historical chronicles of the nobility that has developed autonomously and as a separate sphere of abstracted reality from natural reality. This was the case with China and Egypt, who held a monopoly on the immortality of the soul, and the earliest of their famous dynasties are built upon Debord 2021.imaginary reconstructions of the past. The rulers of these empires, as the owners of the private property of history—protected by a mythical past, make use of myth to prove the legitimacy of their claim to rule. The intention is to be understood as the earthly execution of Mythic commandments would later be repurposed by religion to continue underwriting the control of power in the spiritual domain, best exemplified by the Holy Roman Empire.mythic commandments. The more they claimed historical ownership over time and tied it to their own mythical chronicles, the more they legitimated their control over power.

The development of mythical history began with the administration of kingdoms that went hand-in-hand with the invention of writing. Mythical history gives time an orientation, a direction, and imbues it with meaning and significance. The emergence of history necessitated a development beyond Mythical time to the temporality of Irreversible time. The linear trajectory of irreversible time presupposes endless economic development linked to the production of surplus value, the Lowercase c-capital in this instance can take the form of money, labor, and time.control of this value in the form of capital, and the political management of the resulting power. Irreversible time is oriented around the succession of the nobility, and its measure of progress is determined by the number of successful successions. The Age of Kings was a profoundly Historical society in that social organization was underwritten by history. It was during this age that history had increasing proximity to everyday existence but the possibility of individual participation grew more elusive. Individuals living in this historical society experienced lived moments as mediated through the nobility or God as facilitator, since the nobility had sole possession of The conception of duty has been a means used by the holders of power to induce others to live for the interest of their masters, rather than for their ownhow individuals’ time was used and allocated—so called ‘duty’.6 The nobility were the only ones to be in a position to have knowledge of, and experience the enjoyment of directly lived events, while those in the city spectate upon what is essentially a conflict over power—witnesses to a story that is not their own; which is to say, they were mere spectators, alienated from directing the most important events that define their lives, and destined to be forgotten. In order for the irreversible time of history to cohere in the collective memory of individuals, there needed to be participation in these officially recorded events (as it was their duty). The wealth accumulated by the nobility was expended on lavish feasts and festivals—best exemplified by the ‘bread & circuses’ comes from Juvenal, a Roman poet active in the Second Century AD. The phrase is a critique of the political class who deliver not public services or policy, but instead public diversions, distractions, or other means of appeasing the populace with trivial or base appeals to amusement or other simple pleasures that make no lasting change or improvements to society.bread & circuses of the Roman Empire7 that created fleeting moments of participatory lived experience mediated by the nobility. The major events of this period culminated in the Crusades.The resulting participation in these events is a recognition amongst individuals as the possessors of a unique present, a period defined by the richness of their own actions, and a home built by their own (mediated) experience. For members of the historical society, irreversible time truly exists, and within it they create memories of their own history as well as the emergence of a newfound fear of being forgotten into the oblivion of cyclical time. The spatial modality of this age was the control of territory, and the weapon of choice was, for the first time, the written word. Ironically, the power of the nobility was legitimated by claims (familial or fictional) to a mythical past. It was during this age that E.g. Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism.monotheistic religions developed and made a compromise between myth and history—one that bridged the gap between cyclical time (as it dominated the sphere of agricultural production), and the irreversible time that was the theater of politics. The religions that developed out of monotheism were the fundamental building blocks universally acknowledged as useful for building new historical societies based on irreversible time. It was during this age where one’s life was measured according to irreversible time, in the form of successive stages of life (childhood, adulthood, old-age), with the consideration of life as a voyage, as passage without return, in a world whose meaning culminates in the spatial elsewhere of According to the Augustinian Proclamation, the Catholic Church in Vatican City was the unitary physical space shared with Heaven (Augustine 1993).Heaven.8 Individuals found the fulfillment of their personal histories within the sphere of the ruling nobility. So, just as the nobility defined themselves by waging war over disputed power, individuals attached their personal historical chronicles to their rulers—thus, the knight and his personal story is entwined with the story of duty to his king. The Age of Kings applies to feudal civilizations in China, Egypt, Greece, Iran, Rome, Europe, Japan, and Latin America.

As long as agriculture remained the primary form of labor during the Age of Kings, cyclical time continued to constrain social life with tradition, which inhibited the development of irreversible time. It wasn’t until the rise of mercantilism that the bourgeoisie emerged, challenging the monopoly on irreversible time.39 It was only then that the irreversible time of the bourgeois economy was brought to bear upon the remaining vestiges of cyclical time, eradicating it at every encounter across the globe. As the bourgeoisie gained control over irreversible time, their labor gradually became a project to transform historical conditions.3 The bourgeoisie was the first ruling class for which labor became a valuable commodity. With the gradual abolition of all nobility, social privileges, and titles, they recognize value only from the exploitation of labor, and have identified the control of the commoditized body of labor as their primary form of capital. These developments culminated in the emergence of the Age of Economic Production.

The Age of Economic Production is characterized by working conditions that were the dominant zeitgeber of daily life. This age emerged during the enlightenment and prefigured the industrial revolution with the inventions of the printing press and the clock tower. Irreversible time limited participation to the nobility up until the period of the The bourgeois revolutions include the English Civil War (1642-1651), the American War of Independence (1775-1799), the French Revolution (1789-1799), the European revolutions of 1830 and 1848, and the unification movements in Germany and Italy.bourgeois revolutions. During this age, irreversible time developed into its generalized form—the inevitable unfolding of events for themselves, crushing any individual in its path. This was the emergence of the temporality of Chronological time: a progression of time marked by the unfolding events of the commodity, and controlled its market imperatives. This is a time of clocks that is measurable, ordered, countable, and structured. The bourgeoisie, as rulers of the economy and specialists in the ownership of commodities, untethered history from the administration of the state and privileged the management of the economy. Increasing literacy and the historical power unleashed by the proliferation of the printing press democratized and diminished the hegemony of irreversible time. Individuals participated in the production and consumption of commodities, which was formerly limited to the nobility.3 It was during the later part of this age that capitalism developed across the globe, universalizing chronological time as a singular history that progresses the same everywhere at once. This is a time belonging to the globalized marketplace. The spatial modality of this age was migration, where migrant labor was the major factor in human movement. People lived where they worked, migrations were predicated on moving to locations with improved working conditions. Proximity to work, as well as citizenship and residential status determined access to employment. In the United States, young people moved from familial support networks to cities with better jobs. Space was a constraining factor in this age, where proximity to arts & culture limited what individuals could watch and listen to. The city was the locality of the arts. The conception of utopia during this age was increasingly secular and socially constructed, resulting in the development of liberal democracy and socialism. It was during this age that the concept of leisure emerged as the temporality of Consumable time. Consumable time is the colonizer of non-working time. It is relegated to a subservient role as a gift that presupposes labor rather than as equal to chronological time—it is free time that is legitimated by work, but not free in the sense of freedom. To maintain these complementary roles, consumable time finds itself laden with false attributions of value, and these moments are segmented into a sequence of artificially distinct events, which are merely undifferentiated moments of time perceived to be In consumable time, the weekend is perceived as more valuable than the weekdays, and the general sentiment that Mondays are worse than Fridays. These moments of consumable time are perceived to be more valuable since the worker is able to consume this time freely.more highly valuable.3

The Age of the Autonomous Spectacle is the ultimate realization of the The ‘End of History’ is a political and philosophical concept that supposes that a particular political, economic, or social system may develop that would constitute the end-point of humanity’s sociocultural evolution. A number of writers have argued that a particular system is the end of history including Thomas More in Utopia, G. W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, Vladimir Solovyov, Alexandre Kojève, and Francis Fukuyama in his 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. Papaïoannou is more optimistic, saying “a time of [historical] arrest is not the end of time”, argues that it can contain the potential for new futures (Papaïoannou 2012, p. 97).End of History1011—a refusal of the progression of any major historical divergence from our extant social organization and temporalities. It is an indefinite postponement of the future. This is an age characterized by commodities that exist for their own sake, external to any human desires, or even society itself. This is an age where the “Because value shapes the actions and interactions of individuals within capitalist society, and because such social activity takes place according to its needs… human agents become confronted and dominated by an antagonistic counter [the economy] that governs society in their stead.” (Bunyard 2018, p. 316, altered).economy becomes autonomous—organizing social activity2 in order to reproduce itself.12 This age was inaugurated with the publishing of Propaganda, was written by Edward Bernays in 1928, incorporated the literature from social science and psychology for the techniques of public communication for the manipulation of the masses. (Bernays 2005).Propaganda13 in 192814, it developed with the ubiquity of television and radio. It was formally declared when Margret Thatcher announced “There is no alternative” (TINA) is a political slogan arguing that capitalism is the only viable system of social organization. It was used by Margaret Thatcher in a speech. Together with Ronald Reagan, they began the era of neoliberal austerity and laissez-faire globalization. “There is no alternative to capitalism”.15 , and echoed by David Cameron: The age finally materialized with the fall of the Berlin Wall, when all alternatives to capitalism ceased to exist.

The temporal modality of this age is Spectacular time, with the perception of time itself as a consumable commodity. Spectacular time is generalized across the globe as a repetition of the same day, a Groundhog Day16, spectacular time is a uniform and equal amount of time fully allocated to the production and consumption of commodities, and the reproduction of itself. This is a time that can only be organized by the specialized interest groups who own the production of commodities. Just as irreversible time was democratized during the Age of Economic Production, the Age of the Autonomous Spectacle democratizes chronological time by granting individuals the ability to create and consume commodities in the general economy (whereas it was once limited to the social elite). This is participation with the historical record, albeit limited to the production and consumption of commodities that increasingly becomes the totality of lived experience.

It is during this age that social media allowed individuals to participate in history The celebrity is the contemporary class that was formerly the role of the bourgeoisie, the ruling class, or the nobility—the appearance of the control of power and influence: The Influencer.as celebrity by ‘going viral’ either among their peers, or more broadly. This is an ephemeral participation in history however, as the attention—or gaze of the public—is distracted by the continual onslaught of spectacular memes. Individual subjects of the viral event are quickly subsumed by the global flows of the attention economy that expands autonomously according to market imperatives. This commoditized form of time segments moments into spectacular time and Pseudo-cyclical time. Spectacular time is the equivalent of work, and pseudo-cyclical time is its’ corresponding free-time. Pseudo-cyclical time is perceived to have more intrinsic value than working time—work is the so-called ‘real life’ the worker must endure. The consumption of these images (media broadly: internet, tv, news, magazines, apps, even academic publications) serve as further advertisements for all other commodities.Any surplus pseudo-cyclical time is increasingly allocated to the consumption of images, deepening the immersion in Spectacle is a pervasive system of mediation that alienates individuals from authentic social interactions and experiences. It is not merely about passive consumption of media but encompasses the entire fabric of society, including politics, culture, and everyday life where reality becomes fragmented and commodified, with images and representations serving as a substitute for genuine human relationships and directly lived experiences (Debord 2021).Spectacle. This time is the realm of the commodity, and the images are the medium with which these commodities act upon our consciousness most efficiently. This is the realm of the attention economy, a battlefield from which the Spectacle mounts its strongest attack. The ultimate goal of this attack is to maintain our attention upon the Spectacle itself, and to increase the time allocated to the consumption of spectacular events. Whereas power in the Age of Economic Production was determined by nation-states, who made their power legible by drawing territorial boundaries, and defining residents and aliens—the Age of the Autonomous Spectacle is one where power is determined by attention, and space is no longer relevant.

The invention of the smartphone is the key development (after the emergence of the internet) that established the ubiquity of spectacular time and cyberspace. The smartphone locates us on the internet all the time. We previously went to the place of the internet and took things away with us, but smartphones push us over a threshold where we need to opt-out of Named ‘cyberspace-time’, cf. Fisher 2020, T00:08:30.spectacular time. With the internet in our hands, in the ubiquitous non-place of cyberspace—we’ve lost the ability to opt-out.17 Airspace is a term coined by Kyle Chayka (Chayka 2016).Airspace18 is the spatial modality of this age: the universal realm of the global market, where local goods, cultures and the places themselves are made accessible to the market, each comparable and homogeneous to better conform to the ease of exchange—and therefore lacking any semblance of its once unique character.3 Airspace is a banalizing and homogenizing force across the globe—where the same tertiary services appear everywhere as workers travel the world demanding the same familiar experiences, creating a banal nowhere.18 This can be seen happening simultaneously, with the reproduction of the same coffee shops, stores, languages, restaurants, styles, and customs across the globe. The emergence of Airspace corresponds with the success of non-location companies like McDonalds, Starbucks, Airbnb, Uber & Lyft, Zoom and VPNs are technologies that negate space itself, as well as the need to travel.Zoom, and VPNs. Workers are no longer tied to their localities, cities, or even countries. Workers can move to their hometowns, move in with families, or move abroad in order to change their working conditions. In this age, the nation-state becomes a barrier to free trade, a barrier to the worker trying to optimize their working conditions. With the obsolescence of the nation-state, corporate power comes to the fore. Corporations are the dominant zeitgeber in the daily lives of individuals. They provide the infrastructure for wages, health care, perks, and even define when, where, and who people socialize with. The corporation is the predominant institution that organizes society. The rise of corporate sociality is built upon the graveyard of community. The ideal worker in the Age of the Autonomous Spectacle is the knowledge worker, the self-starter, who has paid for their own training and whose primary task is to produce their own psyche: an The achievement-subject refers to individuals who have transitioned from being obedience-subjects in a disciplinary society to entrepreneurs of themselves in an achievement society. These individuals are driven by a task-oriented compulsion towards constant productivity, self-improvement, and overachievement. They are guided by a positive social milieu that emphasizes “Yes, we can”. This condition ultimately leads to anxiety, exhaustion, burnout, and depression (Han 2015).achievement-subject19 who is expected to have little inputs and produce maximum outputs, with little management, and produce surplus value that consistently goes beyond ‘meets expectations’.

Temporalities of Time

The perception of time is a fluid modality of human thought. A temporality is a collective psychology that dominates the whole mass of society.20 These psychologies shift across periods of time and space, much like an age, a temporality is more keenly felt in the city than in the country. One temporality comes to the fore as another recedes, but one is always more dominant. The dominant temporality of any society is determined by its stage of human social development. During the Age of Cyclical Nature, time was humanized and therefore any individual was able to participate in the historical events of their own time. After the emergence of irreversible time, the individual could no longer meaningfully participate in the lived historical events of their own period, as those events are no longer controlled by those at the base of society.

Cyclical time shaped peoples understanding of time as they encountered naturally cyclical seasons, and according to the patterns of local flora and fauna. It is a perception of time as the passage of the labors of a people in sync with naturally occurring transitions.

Mythical time is perceptually the same as Cyclical time, but underwritten by a claim to ownership of that time by a nobility that has taken ownership of the historical record.

Irreversible time is the perception of time as a linear series of events and developments occurring in the realm of war, economics, technology, knowledge, and yet limited to the personal chronicles of the nobility. It is qualitative. Irreversible time is a temporality whereby the ruling class records their personal histories with narratives—those personal events, conquests, wars, battles, and the administration of their kingdom. Irreversible time is the official time that is contested in clashes between foreign lands. Irreversible time is thus alien to ordinary individuals, something they don’t seek out and something from which they had thought they were protected from. These events mark changes in the historical record that provide a framework for individuals to understand their place within that history.

The early ages we’ve described each correspond to a single temporality. In the later two ages (the Age of Economic Production and the Age of the Autonomous Spectacle, respectively) two temporalities emerge that exist simultaneously. One of these temporalities always corresponds to the In Debordian terms, ‘time of production’ (Debord 2021).time spent working and one corresponds to valorized time (free time that is highly valued by individuals). Individuals experience these temporalities distinctly, and oscillate between them on a day-to-day basis.

| Working time | Valorized time | |

|---|---|---|

| Age of Economic Production | Chronological time | Consumable time |

| Age of the Autonomous Spectacle | Spectacular time | Pseudo-cyclical time |

Chronological time is linear and quantitative. It is segmented, measurable, ordered, and counted. It is the time of clocks, of hours, minutes, seconds, milliseconds.21 Chronological time is the Chronos, it is scheduled and planned in advance, knowable and quantitative.22 It is the time of work.3 Chronological time atomizes the moment, Equivalent time where every interval is equivalent in value and therefore indistinguishable as abstracted units of time, which are, in reality, merely their use value for exchangeability (Debord 2021).where every interval is equivalent in value and therefore indistinguishable.3 Chronological time has no duration, and produces no memory, it is unmemorable time but not forgotten—it is always inscribed into the historical record. Chronological time is understood as a sequence of the same uneventful ‘nows’ that repeat over and over again to the point where each working day is interchangeable with the next. Chronological time is the complement to consumable time, and the opposite of Lived time.

Debord uses the term ‘Pseudo-cyclical time’ when discussing the freely consumable time of the worker that is the compliment of time spent working.Consumable time is the time returned to social life as a by-product of the work accomplished during chronological time3. Consumable time is chronological time disguised so it may be consumed freely by workers. It exhibits the same characteristics, namely equally segmented, fungible units of time—the qualitative dimensions of which are suppressed in favor of quantitative equality. Since this time is the complementary by-product of work, it therefore maintains the hegemony and legitimacy of work. It is a commoditized version of Lived time.

Spectacular time is the ultimate realization of the End of History—a refusal of the progression of any major historical divergence or change to the dominant temporality. It changes our perception of time, Twitter is the perfect example of a ‘screaming low-level panic’ (Fisher, 2020).creating a panic-temporality.17 It enforces a state of constant anxiety akin to entrepreneurialism, a form of precarity where we are compelled to continually hustle and market ourselves even when we have stable jobs. This temporality appears across the globe as a repetition of the same day, a uniform and equal amount of time fully allocated to the production and consumption of commodities, and the reproduction of Spectacle. In spectacular time, we never have the time to sit back and think, to plan for the future—all time has been accounted for, and the future has been foreclosed. This is a time that can only be organized by the specialized interest groups who own the production of those commodities. Spectacular time is an objective religion with dogma, ritual, and the imposition of scripture as fact—these take the form of best practices, productivity optimizations, and quantified success, respectively. This isn’t a subjective religion that is lived and felt, but one that colonizes life. It is a religion that is submitted to from the external doctrines of the economy.

Pseudo-cyclical time is the complement to spectacular time, a time valorized for the ‘free consumption’ by the workers in the Age of the Autonomous Spectacle. Pseudo-cyclical time is experienced as cyclical time, returning to the The natural zeitgebers are the cyclical rhythms of cyclical time: day and night, the procession of the seasons, the intervals of farm work, the cycle of harvests, festivals, and holidays.zeitgebers that regulated the intervals of pre-industrial societies. It builds upon the vestiges of cyclical time as a foundation and generates new variations: day and night, weekly work and weekend rest, and the cycle of fashions, television shows, holidays, and periodic vacations. It is defined by the continuation of the rationality of the enlightenment combined with the demand for data that arose out of the attention economy. Pseudo-cyclical time is itself a consumable commodity, one which has combined all aspects of the social life which were formerly separate: private life, economic life, and political life. This combined time of contemporary society is the raw material to be consumed by the worker however they see fit, but only as inputs to a set of ever-expanding products on the market of socially controlled schedules of the attention economy.

There are two more temporalities, these are the unmemorable, the unaccounted for, and therefore the untheorized. These two temporal domains are the wilderness of time, at once wild sites of potential and yet vulnerable to commodification.

Reproductive time is the time used to reproduce the worker every day.

This is the time required to acquire daily food, clothing, and shelter.

It is the lived experience of commuting, doing chores, cooking, and eating.

It accounts for adequate rest and sleep, maintaining one’s health, childcare, relationships, and community.

It is the equivalent to the time spent surviving in nature—foraging for food, searching for shelter, but set in a modern milieu—shopping, chores, and conducting economic transactions.

Reproductive time is always subject to the dominant time of its age, be that irreversible time, chronological time, or spectacular time.

The economy considers reproductive time as a secondary concern.

As such, health, aging, and childcare are continually sidelined by the economy as externalities that have no bearing on the production of products and services.

Reproductive time is presented as the realm of the domestic, as feminine, and as such is considered invisible and intuitive—which is to say, lacking in thought and rigor.23

Reproductive time is, in fact, the opposite—

To quote Marx describing the revolutionary proletarian: ‘I am nothing and I should be everything.’ (Marx 1975, p. 254).it produces the visible workforce,

and a lot of emotion and thought is put into care for the people who become the fundamental basis of the economy.23

According to Angela Garbes:

Garbes 2022, p. 14.Love and care, like social change, are slow and follow circuitous paths that take days not hours, years not months. The work may seem inefficient, but love doesn’t play by the same rules as the economy.

23

While work is perceived as ‘apart from life’, and ‘free time’ remains perceived as ‘more authentically real life’, the lived experience of reproductive time is cut off from ‘real life’, remaining undocumented and unaccounted for on any personal narrative.

This deprives daily life of language and as a formal concept, and it lacks any analysis of what events occurred within its own past.

Reproductive time is the real time of life, but one that is misunderstood, smothered, and forgotten—to the benefit of the false consciousness of spectacular time that is the memory of the unmemorable.3

Reproductive time is the primary site of recuperation by neoliberal capitalism as it continues to colonize this time.

It appears across the globe with the defunding of any social services that support reproductive time.

Concrete examples of this include the defunding of public education and the increase of private schools and private childcare; the increase in the costs of college education, the politicization-of & elimination-of reproductive healthcare; the increase in health insurance costs and its decreasing coverage; the reduction of subsidized food and housing programs; the privatization of health services such as the NHS in the UK, and the consolidation of hospitals and outpatient clinics in the US.

These reductions come at the expense of workers, and the costs are borne by workers in terms of both time and money.

The ideological goal of these actions is twofold: shift the burden of reproductive time onto workers by eliminating services and shifting them to the private domain while corporations capture increasing profits by decreasing operational costs.

I chose to use Debordian term ‘Lived time’ because it has the connotation of actually living. Other have used the Greek word ‘kairos’ to describe such moments, see Odell 2023.Lived time is the freest, most fun, most creative mode of time experienced.3 Lived time is the Kairos, Debord 2004, p. 62.those strategic points in which we are obliged to sieze the moment and act,24 those nonlinear and qualitative moments that dynamically stretch and contract with our emotions, engage all our senses, and requires full participation.22 Lived time are those Known as ‘ecstatic time’ in Being and Time, the word comes from the Greek ékstasis—to be ‘outside of oneself’. See Heidegger 1962.moments of ecstasy experienced during leisure, play, focus, intense emotions, and erotic rapture.4 It is a time experienced without the awareness of time passing. Lived time are those moments when we do something for the hell of it, escaping the rigid order of the schedule. Lived time is a The ‘space of play’ is Graeber’s term for a distinction between play and games, where play is free, creative, and open-ended, while games are rigid, repetitive, and closed-off. Graeber suggested that play underlies art, science, conversation, and community, while games are the preferred method of bureaucracy. He emphasized that the key distinction between games and play is the presence of rules, with games being defined by their rules, while play is defined by its lack of rules (Graeber 2015).space of play that is free, creative, and open-ended.25 Athletes, artists, and creatives have converged on describing this time as “a state of flow”—a total state of immersion in activity. Lived time is unhurried, a time in which people can pursue their own projects, at their own pace. These projects may not lead to a predetermined goal, but gradually become unto themselves, absent a goal—done for their own sake. When we say we “have lost track of time”, it is often due to the experience of lived time. The feeling of lived time at its most intense can be depersonalizing, we only realize how absorbed we are when we emerge from it. Lived time is never scheduled and always late. It is here where we abandon the utility-value of time as money, and it is where past, present and future coalesce into duration21—the perception of memorable times distilled into a narrative that chronicles one’s life. Lived time is fundamentally useless, ephemeral, disposable, and therefore cherished—that singular characteristic beyond value. Lived time is experienced for its own sake—not guided by instrumentality or utility. It is a time that uniquely gives us a sense of our own mortality.21

Instrumentarianism and The Perpetual Present

The Perpetual Present is our contemporary social milieu—a period without duration that never changes, it is a temporality where the past is irrelevant, and The Perpetual Present is the reification of time itself.the present moment is spent determining a future that isn’t our own. Unlike the circle in the cyclical time of nature, and the line in the irreversible time of history, the perpetual present is a point of singularity collapsed into a time we call ‘now’. The perpetual present is the period at the End of History.

The

The autonomous economy is an economy which has shifted from the satisfaction of human needs to the generation of pseudo-needs in for its own sake, external to any human desire, or even society itself, organizing reality in order to reproduce itself.autonomous economy

privileges the perpetual present which is concentrated as a cascade of urgent ‘nows’ that bury the past and obscure the future.

There is no felt duration between past and future when the now is in ubiquitous crisis.

The ubiquity of this temporality creates a dominant social order—one in which we

scurry to meet the demands of our quantitative culture.

21

Our lives increasingly exist in the perpetual present, where moments are sold according to the ticking of the clock.

Time is money, time is getting things done, and yet, at the end of the day we cannot account for where our time went.

A society dominated by continual busyness is a social life that is permanently anxious and

“It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism” a quote attributed to Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek (Fisher 2009).too distracted to imagine a future.2627

The perpetual present is haunted

, according to Mark Fisher,

by

lost futures that the twentieth century taught us to anticipate…

the disappearance of the future meant the deterioration of a whole mode of social imagination:

the capacity to conceive of a world radically different from the one in which we currently live.

It meant the acceptance of a situation in which culture would continue without really changing.

28

This is a society deeply networked by smartphones, and an onslaught of tasks that ruthlessly undermine any sense that time can ‘congeal’ due to informational saturation.

The more information we are exposed to, the more we are subject to the durationlessness of the perpetual present, and our focus narrows onto specific instrumental objectives.21

This instrumental attention prioritizes time solely as a means to attain certain ends: we allocate time for tasks essential to perceived survival, tethering our actions to the ticking of the clock.

This gives us a diminished sense of duration, and therefore diminished memory—a society of amnesiacs in pursuit of productivity for its own sake, in service to an economy that operates for its own sake.

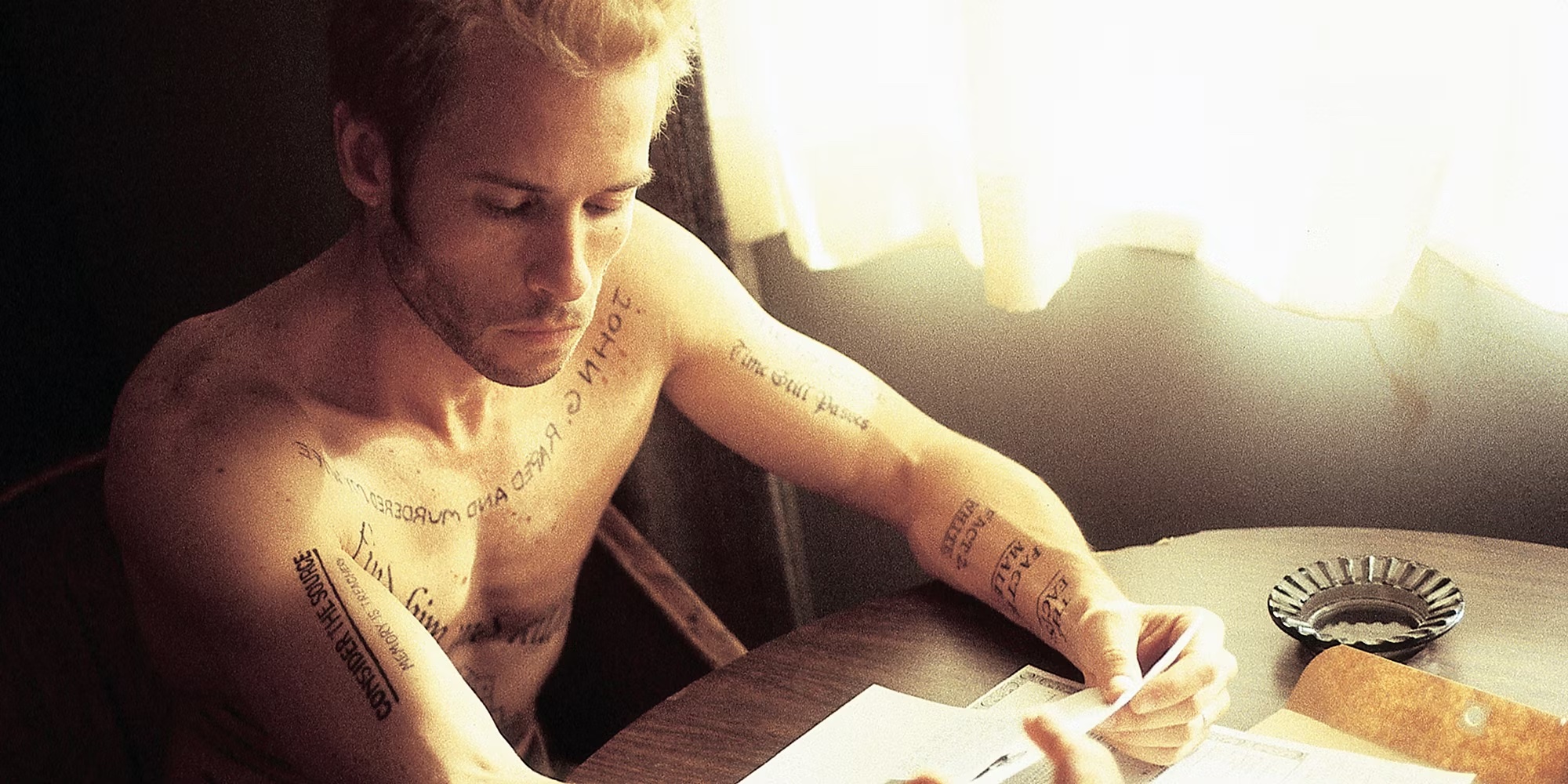

In the perpetual present we are all Leonard, the protagonist in the 2001 film Memento.

Cf. Nolan 2001Here’s the thing. You see, I haven’t told you about his condition.29

Leonard has anterograde amnesia, a result of a violent home invasion that left him injured and his wife dead. The traumatic memory of this murder drives Leonard’s quest for revenge. Despite his condition, Leonard is portrayed as smart, determined, and capable. He is the exemplar of the achievement-subject: someone focused on achievement for its own sake, the task of increased achievement. Leonard exists in a perpetual present brought on by amnesia. Spoilers: spoiler alert in three… — two … — one … — once he has gotten his revenge, he must answer for himself: What is next, and to what end? To this, he refuses to answer, and instead changes his own memory by editing the notes that document his own past. His perpetual present is constructed with lies and selective memory. He continues his task beyond completion, beyond achievement. Leonard is the achievement-subject taken to its logical conclusion.

Our perception of the perpetual present exhibits two key characteristics. Firstly, time is exclusively tied to the fleeting and present moment. Secondly, this present moment becomes illusory, infinitely divisible, and laden with an ever-expanding array of tasks—becoming infinite. Pursuing this logic leads to the imposition of an unattainable burden, resulting in widespread anxiety and burnout.19

Leonard’s amnesia inoculates him from burnout. Without memory, without any meaningful sense of the past, Leonard maintains an infinite state of productivity without burnout. The TV show Severance expands upon this idea, where employees volunteer to have their brains surgically segmented, thus splitting one’s work life from their personal life—they, quite literally, have no memory of their workday. In the show, The procedure is legitimated as beneficial to mental health, and its’ effect produces a docile, burnout-free workforce.30

We are all Leonard in the perpetual present that is continually demanding ‘more’. More things to do, more tasks to complete, more labor to be expended, more psychological effort, more status to achieve—nothing is ever complete, and nothing is ever enough.21 We, unlike Leonard, are not immune to anxiety, depression, exhaustion, and burnout. Leonard exemplifies instrumental attention, an attendance to goals and outcomes that is typical of the achievement-subject. These goals and behaviors are—much like Leonard—vulnerable to manipulation by the operant forces of Spectacle and surveillance capitalism.

Zuboff defines surveillance capitalism as the utilization of big data, AI, and data-driven technologies to subtly modify human behavior remotely and at scale towards economic ends.31 The smartphone inaugurated the era of big-data surveillance and gamified behavioral modification using gadgets. Twitter’s “pull-to-refresh” UI gesture that leverages variable rewards, much like a slot machine, triggers addictive behavior as a way to increase user engagement with the timeline. Facebook employs similar psychological methods with the “red dot” notifications that keep people checking their phone for the next new thing.32 Youtube & Netflix discovered that auto-playing the related videos dramatically increased views.33 Zuboff defines According to Lacan34, the ‘big Other’ represents a kind of ideal observer or societal norms that individuals perform for, shaping their behavior and expressions to conform to social expectations (Evans 1996). Žižek35 further explores this concept by delving into the enigmatic nature of the ‘big Other’, questioning its demands and highlighting its role in shaping desires and behaviors within society (Žižek 1989).’Big Other’ as the global physical architecture of computerized and networked technologies that achieve a pervasive and unprecedented means of behavioral surveillance. This creates a new form of Instrumentarian power that operates through the manipulation of individuals’ behaviors, preferences, and actions based on predictive data derived from technological tools—ultimately serving the commercial interests of corporations.31

Contrary to Orwellian depictions of oppressive surveillance technology that maliciously watches our every move, instrumentarian power doesn’t rely on forced control or subjugation but rather on individuals who willingly interact with technology in ways that lead them to progressively disclose personal information and behaviors over time. Zuboff’s Instrumentarian power aligns with Debord’s concept of the Integrated Spectacle in Comments on the Society of the Spectacle he described it as a fusion of the Diffuse and Concentrated forms, characterized by intensive technological development, continual personal re-skilling, and an integration of state and economy that mirrors how surveillance capitalism intertwines technology with economic interests to monitor and influence individuals’ voluntary experiences for profit. It is a prescient description of instrumentarian power (Debord 1998, ch. IV). Voluntary participation is both far more effective and efficient at subduing the masses, since it appears to empower individuals through improved productivity and consumer choice.14 Technology companies leverage cloud computation, big data, artificial intelligence, and behavioral economics to monitor and manipulate experiences for the purpose of commodifying users’ private data and attention to keep users engaged.31 Ultimately, instrumentarianism is a power over time, a unilateral claim to the future,31 a power to sell future behaviors to advertisers—all while burying the present in a cascade of banal trivialities.

The Rise of the Zeitzombie

The extreme busyness of the perpetual present saps us of vitality and leaves us without a strong sense of personal identity. We have been seduced into the culture of hustle & grind, we have worked so many long hours that our imagination is devoid of anything outside of work.

”There is a sort of dead-alive hackneyed people about, who are scarcely conscious of living except in the exercise of some conventional occupation.”36

Robert Louis Stevenson An Apology for Idlers

said Robert Louis Stevenson. Accordinng to Han,

Han 2015, p. 50.When life is devoid of value, it must be kept healthy at any cost, health becomes self-referential without any greater purpose.

Health is the new goodness in a society that doesn’t know what good is…

The people of the achievement society are zombies, they are too healthy to die, and yet too dead to live.

19

This is all to say,

We are all Leonard, we are—the zeitzombie.

Zeitzombie zeit·zom·bie, IPA /ˈzaɪtˌzɑmbi/ A conjunction of the German zeit for ‘time’ and the Kikongo word zumbi for ‘fetish’. The zeitzombie A form of commodity fetishism applied to time: as “the confused identification of particular objects [time] with the attributes that are accorded to them as a result of the social relations in which they are located”. Bunyard 2018, p. 296.confuses their time with money. The zeitzombie is a living corpse reanimated by productivity and busyness. They are those who claim to have no time. The zeitzombie is created when a life is drained by the vampire of neoliberal capitalism, converting living flesh into Dead labor is labor power that has been expended into a product, a widget, a machine, or even a factory (Marx 1867).dead labor.37 Symptoms include: the glorification of work, a protestant work ethic, and a proclivity to do things for the sake of getting them done, and dedication to keeping healthy at any cost. Other symptoms include a resistance to sociality, a fear of daydreaming, and the elimination of boredom.

The zeitzombie is the product of our collective proclivity to say ‘yes’, it’s an

Positivity, according to Han, is “the societal focus on positivity and achievement can lead to an excess of pressure and expectations, making it difficult for individuals to manage negative experiences and ultimately resulting in burnout.” (Han 2015, p. 1). Cf. Fisher 2014 who calls it a “permanently multitasking, permanently distracted state of being”.excess of positivity.1927

As the achievement-subject, we say ‘yes’ to the urgency of the perpetual present, we say ‘yes’ to performance improvements at work, we say ‘yes’ to optimizing our health, we say ‘yes’ to answering late night work requests, we say ‘yes’ and pickup those side jobs.

According to Jenny Odell:

Odell 2019, p. 15.Every waking moment has become the time in which we make our living… time becomes an economic resource that we can no longer justify spending on ‘nothing’.

38

There is no ‘work-life balance’ for the zeitzombie, when all of life is work:

producing our work, producing our bodies to better produce work, producing our psychologies to identify with the production of work.

According to Fisher:

Fisher 2009, p. 34.

Work and life become inseparable.

Capital follows you when you dream.

Time ceases to be linear, becomes chaotic, broken down into punctiform divisions…

To function effectively as a component of just-in-time production you must develop a capacity to respond to unforeseen events, you must learn to live in conditions of total instability, or ‘precarity’.

26

There is a type of zeitzombie that exists merely to solve ‘real world problems’—the techno-optimist.

This species goes as far to claim that even

death can be fixed with AI

39

to quote Andreessen

—presupposing death as a problem in need of a solution,

and yet offering no vision for what life could be.

Give us a real world problem, and we can invent technology that will solve it.

39

they say. Everything is a problem to be solved, and technology is the solution to every problem,

and yet the zeitzombies propose no reason other than for the sake of inventing new technology.

They offer no vision for a good social life—only a world in which

Emphasis in the original. For the techno-optimists, work is heaven, and in their manifesto there is no meaning, nor life, in their section called “The Meaning of Life”, cf. Andreessen 2023.man was meant to be useful, to be productive.

39

, in their words.

For the zeitzombie, there is no life outside of work, and death is a problem that needs to be solved in order to guarantee future productivity.

The zeitzombie is the techno-zealot—

quoting him again,

we believe intrinsic motivations– the satisfaction of building something new…,

the achievement of becoming a better version of oneself

,

these are the words of the achievement-subject, true believers in the coming of the

Their techno-Messiah is the General Artificial Intelligence (AGI). “We believe Artificial Intelligence is our alchemy… [AI] can save lives” (Andreessen 2023).AI techno-Messiah40

who will unleash endless productivity for its own self-development, or

Roko’s Basilisk is a thought experiment that proposes a superintelligent AGI who punishes anyone who doesn’t actively contribute their lives to the development of itself. (Roko, 2022)punish those who refuse to work for its own benefit.

And so, just like the knights in the Age of Kings whose personal chronicle was bound by duty to their lord,

the techno-optimists are bound by duty to accelerate The Singularity: the emergence of their AI god.

The zeitzombie has internalized corporate claims that Fisher 2009, p. 40.‘satisfactory’ is not enough, they intuitively understand that schools, jobs, and even gig apps will undertake performance improvement plans unless they’ve met ‘exceeded’ or ‘excelled’ performance. They are therefore compelled to excel beyond satisfactory in all institutional environments. This drive to continually excel and constant precarity leads to a diminished sense of life and yields to the simple concern for survival. This is the ‘logic of increase’ that subsumes all notions of a good life in the realms of work, money, health, knowledge, relationships, and community. This logic manifests as a fear of falling down the social order that is amplified by social media as we scroll through friends’ and celebrities curated image of “what life could be”.22 The condition of the zeitzombie applies equally up and down the social spectrum, from the working-poor to the Elon Musks of the world, everyone is time-poor when we all live to work.

With the conveniences offered by smartphones, we willingly forfeit the separation that work and life once had. These technologies expand the legitimate claims to our time inside and outside work, we are expected to be Odell 2023, p. 65.reachable by anyone anyplace and at any time.22 The work-life balance is blurred even more when you consider the impact of technology on leisure. Vacation once meant leaving the physical place of work behind, now we must ask ourselves what is vacation when you can work remotely from vacation? When there is no clear demarcation between work and where we are in space, leisure, as it was understood, is now less definable—just as the concept of ‘home’ is less obvious when we work from home. That which was formerly private space is no longer a place of refuge.

Depression, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Borderline Personality Disorder, and burnout are the dominant psychological pathologies at the beginning of the twenty-first century.19

The zeitzombie is ultimately a victim of a society that privatizes social problems,

Fisher 2015, p. 21.treating them as if they were caused only by chemical imbalances in the individual’s neurology and/or by their family background—any question of social systemic causation is ruled out.

26

says Fisher.

Society puts the responsibility of managing social problems onto the individual as personal failures.

Failure to socialize, failure to manage time, failure to manage one’s own mental health—and yet depression is

the

, according to Han:

Han 2015, p. 10.pathological symptom of late modern human beings failure to become himself.

19

Thus, as we forfeit our claim to time, and forfeit our claim to space, we forfeit our claim to memory, we forfeit our claim to life—and thus we all become the zeitzombie.

Leisure as Refusal: The Power of ‘No’

Over the last

40 years corresponds to the neoliberal era of economic deregulation that started with Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore, then Reagan in the US and Thatcher in the UK; Yasuhiro Nakasone in Japan, and Deng Xiaoping in China pursuing ‘Socialism with Chinese characteristics’.40 years

we’ve seen an accelerated emergence of implicit and explicit forms of negativity and refusal, especially in more concentrated societies like Japan and China.

The

The Japanese economic miracle of the 1980s was characterized by easy credit, unbridled speculation, and soaring asset prices, which eventually led to a bust in the early 1990s, resulting in a deep recession.Japanese economic miracle

and the subsequent stagflation of the 1990s created a challenging environment for young people, especially university and high school students, who faced immense pressure to succeed in a society where work achievements were hamstrung by loyalty and seniority.

The intense competition and high-pressure environment led some individuals to withdraw from society as a coping mechanism, resulting in the condition of the

The term ‘hikikomori’ was first used in 1985 to describe retreat neurosis and social apathy, it originated in Japan and refers to a form of social withdrawal where individuals, typically young adults, isolate themselves from society for extended periods, often staying at home and avoiding social interactions (0xADADA 2003).引きこもり.42

The

The 996 working hour system (996工作制) in China requires employees to work from 9:00 am to 9:00 pm, 12 hours per day for 6 days per week; i.e. 72 hours per week. It is still widespread as of 2024.996 working hour system

in China resulted in exhaustion, burnout, mental health conditions, and strained personal relationships among workers.

This led to the emergence of the

躺rotate the world 90 degrees, and people will discover this unspoken truth: the one who lies flat is standing, and the one who stands is crawling.

43

Tang ping advocated for a recognition of the slavery inherent to existing working conditions, and rejects the societal expectations tied to relentless work hours and material success.

Tang ping and its spiritual successor

摆

To resist the dominance of spectacular time and the perpetual present, we must collectively take responsibility to determine how we use time & space—and to what ends, otherwise the instrumentarian power will allocate our lives to its own ends. To do so, we can try embracing negativity. By negativity we don’t mean melancholy or pessimism, but rather our ability to self-determine one’s life by negation, or the change of what we are with a view to being or becoming something else. Without negativity we do not have freedom.19 Neoliberal capitalism encourages human beings to be defined by activity and action—‘yes I can’ (an excess of positivity), often from pressures outside onesself. Negativity is the opposite, it is the power of ‘No’—the power to choose.

The power of ‘No’ is predicated upon the increases of productivity in the last 40 years without a corresponding increase in wages or a decrease in time spent working.

American households are working more overall today compared to 1980, putting in an average of nearly 4 more weeks of work annually.

This is largely a result of women having shifted from reproductive labor to employment.45

This increase in productive-time yields surpluses in the form of profits for corporations, and yet lost time for ourselves.

According to Marx,

Marx 1973, p. 628. C.f. Debord 2021 thesis 1.The wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails presents itself as an immense accumulation of commodities.

46

The real measure of wealth in a society that calls itself ‘developed’ is not money nor commodities,

but rather, disposable time—which is to say the

Bunyard 2018, p. 220.collective potential to actualize qualitatively differentiated moments of lived experience.

2

We say ‘No’ and refuse to give more time to the production and consumption of commodities.

When we think of time in terms of hours, minutes, and seconds, we mistake these mere referents as the thing in itself—which is to say, we mistake the map for the territory.

The result of this perception is a collection of social problems caused by

Odell 2023, p. 120, cf. Bergson 1944conceiving of the true nature of time as stemming from wanting to imagine discrete moments sitting side by side in space.

2247

said Bergson.

This thinking traps us into the anxiety of ‘losing time’, of ‘time passing’, and the loss of productivity that motivates the achievement-subject to produce their own self-exploitation.

Many of our contemporary social conditions come from auto-disciplining ourselves into an inability to say ‘No’.

The power of ‘No’ allows us to move towards temporal self-determinacy.

This is temporal negativity, a ‘No’ to things that hijack our time, a ‘No’ to instrumentarian power.

The task of ‘No’ is to consciously (and collectively) self-determine the goal of human activity and act towards the realization of that goal.

The individual’s concrete activity in leisure (the means) is directly connected to its own action (the ends), which is to say, it is done for its own sake.

This is the fulfillment of unity between theory and praxis that moves beyond the economic determinism of the autonomous economy to our own,

communal, self actualization in time and history.

A path forward may be to extend the collective understanding of leisure as a way to establish

Bunyard 2018, p. 211.a condition of unity between conscious human agents (subject) and their own objective historical existence (object)

,

which is to say—we can become who we want, as we want, in our own time.

‟Rather, her [Sarah Connor] knowledge of the material conditions that produce this awful future have radicalized her, she has embraced her situation not as a passive observer, but as an agent active within history, fully conscious of the power that the present has over the future.”48

Adam C. Jones Radicalized by the Future: Are We All Sarah Connor?

What can revitalize us, is thinking.

Thinking takes time that requires lingering, deliberating, weighing up possible alternatives, and patience.

All these are active forms of ‘No’ that resist attempts to turn us into passive beings that obey without resistance.

If we don’t, we face hyperactivity and its consequences: anxiety, depression, exhaustion, and burnout.

‘Hyperactivity’ is reactionary, it blindly reacts with unthinking efficiency—it lacks in activity since it presupposes immediacy, rather than real activity of thought, which requires time, effort, and delay.21

We can borrow practices from Zen meditation, where one attempts to achieve

Han 2015, p. 23.the pure negativity of not to—that is, the void—by freeing oneself from rushing

,

from intrusive thoughts.19

We need contemplation: the mode of

Merrifield 2008, p. 165.holistic thinking that considers everything,

the thinking that is the product of daydreaming, adventures in the mind, meditative thinking that is often useless but done for its own sake.49

We need activity of thought—the non-time of thinking without rules, without best practices, using intuition which brings into existence new territories of ideas, language, and actions that could never have been predicted.

To say ‘No’ is to reject the dominant temporality and embrace time for its own sake, a time that is ours.

What can ‘save’ us is the revival of the sabbatical, a period of relaxation and observation. The sabbatical, according to the Hebrew Bible, occurs after six years of planting and tending one’s fields, you let them lie For more on fallowing, see Kuzmanović 2024.fallow51 on the seventh year—to let them grow wild without harvest or tending. It is a year of rewilding of the land, just as we may similarly re-wild our thoughts. Farmers took sabbatical on a rotating basis, and other farmers pooled resources to support the farmer who was observing sabbatical. The sabbatical is a period of listening, not speaking; watching, not doing. It’s not about refreshing oneself to improve future productivity, or reflecting on the past. It’s about reorienting oneself to the present moment free from outside demands.

What can ‘save’ us is idleness. Idleness and imagination are essential to our wellbeing, they’re the wellspring of mental clarity, and the backstop for memory. Idleness is the space of play, it opens a time that engages all the senses and full participation. It allows for activity for its own sake, without ends or instrumental reasoning. The activity is self-determined and open-ended.

What can ‘save’ us is boredom. Boredom is the peak of mental relaxation19 and acts as a gravity well for contemplation. We can turn off our smartphones and de-network ourselves. We can resist the mechanization of the supernormal stimuli, we can resist our reactionary impulses that drive social media by means of technological abstinence, it could be Orthodox and traditionally observant Jews do not use lights, electrical appliances, or any other electrical devices on the Sabbath (Fri night to Sat night). This is because using electricity violates the biblical prohibition on performing “creative labor” (melachah) on the Sabbath.ceasing to use technological devices, or it could be by creating spaces that are free from commercial technology.

What can ‘save’ us is leisure.

True leisure is the experience of free and undetermined Lived time.

By free we mean freedom, a mode of living that is not determined, modes of life free from necessity and purpose.52

This is a leisure that is the opposite of

vacation, which became instrumentalized leisure, sold as a packaged product to refresh us for our next stint of work.

Leisure provides

Odell 2023, p. 106.a moment of perspective on the grander reality

22

where we can engage with both past and future.

Through leisure we reanimate our sense of duration by reintroducing lived time into our lives.

Leisure is the source of happiness, real meaningful happiness comes from the whimsical, where we engage in practices and projects which are not subordinate to an economic imperative (those things which are trivial, superfluous, and gratuitous).

Put simply, leisure is to luxuriate in fun.

We demand a leisure of the commune, a leisure that isn’t the personal responsibility of the individual, but a leisure that is a common good for all people.

This is leisure-as-public-park: where we

Odell 2023, p. 95.have demarcated space as one free from private ownership… free from the work of optimizing oneself.

22

What can save us is to Income inequality is to such a degree that no amount of working reduces ones poverty. So our question remains, why work? “the same question is about to be posed again everwhere: how can we make the poor work, when illusion has disappointed and when force has been defeated? (Debord 2021, Preface to the Third French Edition)Never Work!3

Cf. Baltasar Gracián, see Debord 2021, ch. VI.We have nothing but time, let’s make it our own.

Bibliography

Footnotes

-

Poe, Edgar Allen. February 3, 2022. “The Imp of the Perverse.” The Poe Museum (blog). poemuseum.org. ↩

-

Bunyard, Tom. 2019. Debord, time and spectacle : Hegelian Marxism and situationist theory. Haymarket Books. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Debord, Guy. & Adams, Ron. 2021. The society of the spectacle. Unredacted Word. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12

-

Heidegger, Martin, John Macquarrie, and Edward Schouten Robinson. 1962. Being and Time. Harper and Row. ↩ ↩2

-

Braudel, Fernand., & Reynolds, Siân. 1992a. Civilization and capitalism, 15th-18th century, vol. 1: the structures of everyday life. University of California Press. ↩

-

Russell, Bertrand. 1972. In praise of idleness, and other essays. Simon & Schuster. ↩

-

Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: the first 5,000 years. Melville House. ↩

-

Augustine. & Dods, M. 1993. The city of god. New York: Modern Library. ↩

-

Braudel, Fernand., & Reynolds, Siân. 1992b. Civilization and capitalism, 15th-18th century. vol.2: the wheels of commerce. University of California Press. ↩

-

Papaïoannou, Kostas. 2012. Hegel (Le Gout Des Idees). Paris: les Belles Lettres. ↩

-

Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York, N.Y. ; London: Free Press. ↩

-

Jappe, Anselm, Donald Nicholson-Smith, and T J Clark. 1999. Guy Debord. University of California Press. ↩

-

Bernays, Edward L. (1928) 2005. Propaganda: With an Introduction by Mark Crispin Miller. New York: Ig publishing. ↩

-

Debord, Guy. & Imrie, Malcolm. 1998. Comments on the society of the spectacle. London New York: Verso. ↩ ↩2

-

Thatcher, Margaret. 1980. “Speech to Conservative Women’s Conference”. margaretthatcher.org. Margaret Thatcher Foundation. (Retrieved March 20, 2024). ↩

-

Ramis, Harold, dir. 1993. Groundhog Day. Columbia Pictures. ↩

-

Fisher, Mark. 2020. Mark Fisher - cybertime crisis. YouTube. ↩ ↩2

-

Chayka, Kyle. August 16, 2016. “Welcome to Airspace”. The Verge (blog). theverge.com. ↩ ↩2

-

Han, Byung Chul. 2015. The burnout society. Stanford Briefs, an Imprint of Stanford University Press. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9

-

Fernand Braudel. 1995. A History of Civilizations. New York, N.Y., U.S.A.: Penguin Books. ↩

-

O’Connor, Patrick. 2021, December. Posthumanism and technology (lecture 12: Byung-Chul Han, technology and the burnout society). (Retrieved March 8, 2024). ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

Odell, Jenny. 2023. Saving time: discovering a life beyond the clock. Random House. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

Garbes, Angela. 2022. Essential labor. HarperCollins. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Debord, Guy. 2004. Panegyric, Volumes 1 & 2, translated by James Brook and John McHale. London New York: Verso. ↩

-

Graeber, David. 2015. The utopia of rules: on technology, stupidity, and the secret joys of bureaucracy. Melville House Publishing. ↩

-

Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist realism: is there no alternative? Zero Books. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Fisher, Mark. 2014. “Mark Fisher: The Slow Cancellation of the Future.” YouTube. ↩ ↩2

-

Fisher, Mark. 2012. “What Is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly 66 (1): 16–24. doi. ↩

-

Nolan, Christopher, dir. 2001. Memento. Newmarket. ↩

-

Stiller, Ben Stiller, and Aoife McArdle. 2022. Severance. TV Series. Apple TV+. ↩

-

Zuboff, Shoshana. 2018. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Public Affairs. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

0xADADA. May 1, 2018. “Against Facebook.” 0xADADA (blog). 0xadada.pub. ↩

-

Bridle, James. 2019. New Dark Age : Technology and the End of the Future. Orca Book Services. ↩

-

Dylan Evans. 1996. An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. Routledge. ↩

-

Žižek, Slavoj. 1989. The Sublime Object of Ideology. Verso. ↩

-

Stevenson, Robert Louis. 2023. An apology for idlers. gutenberg.org. (Retrieved March 8, 2024). ↩

-

Marx, Karl. (1867) 1990. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. / Vol. 1. Harmondsworth: Penguin in Association with New Left Review. ↩

-

Odell, Jenny. 2019. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Melville House. ↩

-

Andreessen, Marc. October 16, 2023. “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.” Andreessen Horowitz (blog). a16z.com. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Roko. March 24, 2022. “Roko’s Basilisk”. LessWrong (blog). (Retrieved 24 March 2022). ↩

-

Leone, Sergio, dir. 1966. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Archive.org. Produzioni Europee Associate. ↩

-

0xADADA. January 1, 2003. “Hikikomori/Otaku Japans Latest Out-Group - Creating Social Outcasts to Construct a National Self-Identity”. 0xADADA (blog). 0xadada.pub. ↩

-

Tangpingist, Anonymous. April 1, 2021. “Tangpingist Manifesto.” Bugs - Chi.st (blog). chi.st. ↩

-

Berardi, Franco ‘Bifo’. 2024. Forthcoming. Quit Everything: Interpreting Depression. Repeater. ↩

-

Pew Research Center. 2016. “The State of American Jobs: How the Shifting Economic Landscape Is Reshaping Work and Society and Affecting the Way People Think about the Skills and Training They Need to Get Ahead.” Pew Research. ↩

-

Marx, Karl. (1859) 1973. Grundrisse : Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Martin Nicolaus. London: Penguin. ↩

-

Bergson, Henri., & Mitchell, A. (1944) 1907. Creative evolution. The Modern library. ↩

-

Jones, Adam C. February 14, 2024. We’re All Running from The Terminator: The Radical Left Versus Capitalism. YouTube. ↩

-

Merrifield, Andy. 2008. The Wisdom of Donkeys. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ↩

-

Donner, Richard, dir. 1985. The Goonies. Warner Bros. ↩

-

Kuzmanović, Maja, and Nik Gaffney. 2024. “Fallowing.” anarchive. Accessed March 24, 2024. anarchive.fo.am. ↩

-

O’Connor, Patrick. 2021, December. Posthumanism and technology (lecture 13: Byung-Chul Han, technology and psychopolitics). (Retrieved March 8, 2024). ↩